American Indian Children Are Facing Racial Discrimination in the Classroom

December 2022

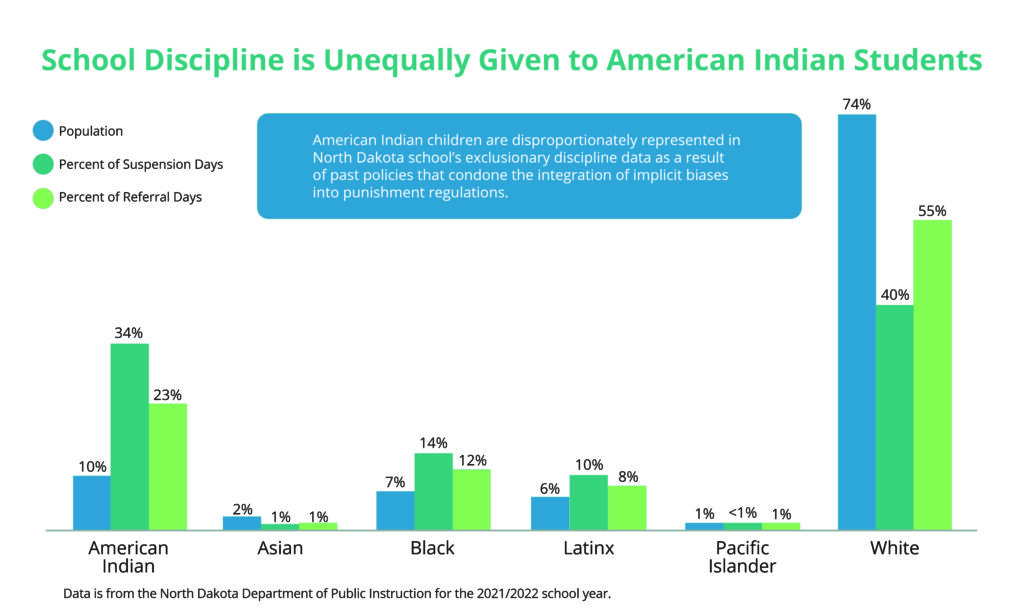

In North Dakota, public schools disproportionately suspend and refer American Indian children to law enforcement. Despite the different suspension rates, research shows that Indigenous and white students display behavioral issues at roughly equal rates in school settings, pointing to a larger problem of racial discrimination in the classroom. Exclusionary discipline practices like suspension or police department referrals result in American Indian children losing vital time in the classroom, making them less likely to graduate. The link between suspension and referrals and graduation is called the school-to-prison pipeline because students are more likely to become incarcerated without a high school diploma.

No Standard Regulations Exist for Exclusionary Discipline

Out-of-school suspensions and referrals are two measures of exclusionary discipline in public schools. In North Dakota, the requirements for suspension and referrals are under local control; the districts decide when they refer or suspend a child. Out-of-school suspension can fall into six categories ranging anywhere from the complete exclusion of a child from attending class or school activities to suspension with education services.1 A referral is when a school employee reports a student to a law enforcement agency or officer, including school resource officers (SROs). All arrests are referrals, but not all referrals lead to arrest. The U.S. Department of Education has changed the definition of "referrals to law enforcement" to include all contact a student may have with officers that could have negative consequences for the student. One consequence of the variation in North Dakota’s regulations in discipline is that children and their families are met with a lack of communication or uncertainty when speaking with schools or SROs.

High rates of discipline are not limited to American Indian children. These increases in disciplinary reports reflects a larger pattern of discrimination against Black, Latinx, and American Indian children nationwide. Discrimination in disciplinary practices affects more than 30,000 Black, Indigenous, and other children of color attending public schools in North Dakota.2 This reflects one out of every four students in North Dakota. American Indian students make up the largest race group at 10 percent of the student population. Indigenous students face the highest disproportionate rates of suspension and referral in North Dakota. About 10 percent of the student population are American Indian, yet Indigenous students make up 30 percent of all out-of-school suspensions and 20 percent of all referrals to law enforcement. Data collected on the three largest counties reflects similar trends as the entire state. In Cass, Burleigh, and Grand Forks Counties, American Indian children were given suspension days at a rate about two times higher than their percentage in the population. All three counties have similar trends for disproportionate referrals of American Indian children as well. For referrals, Cass County has the largest disproportion where American Indian children make up only 3 percent of the student population, but receive 11 percent of all referrals. It is important to remember that behind each statistic, every number represents a child with unique circumstances. It also does not fully embody the emotional and financial repercussions that families face when in a position to defend their children. Exclusionary discipline often only succeeds in revealing the inequities that exist between families that can afford to spend valuable resources on challenging harmful allegations and those that cannot.

Discriminatory Education Policies Have Existed for Hundreds of Years

Policies that open the door to discrimination against children of color are not new. Indigenous children have faced them as early as the 1800s. The United States enacted policies such as "the Indian Civilization Fund Act" and the "Peace Policy" that supported boarding schools designed to assimilate American Indian children through the erasure of their language and culture. Many people still experience the effects of these harmful policies today in the form of intergenerational trauma. Yet, policies that enable discrimination still exist today. They have just taken different shapes as societal norms shift. One example of this shift is the move away from corporeal punishment to "zero-tolerance policies." These policies made it possible to punish all children using exclusionary tactics regardless of the severity of the action. These punishments unevenly fall on students of color and contribute to racializing the school-to-prison pipeline.

One alternative to exclusionary discipline is restorative justice, where students are empowered to focus on mediation and agreement rather than punishment. Students who break a rule must take responsibility and make restitution to hurt parties. According to a National Education Policy Center brief, restorative justice narrows the racial disparities in how educators’ issue exclusionary discipline. Some schools in North Dakota have begun to use alternative methods of discipline with some success, but as of now, there are no statewide regulations.

Biases in the Classroom Cause Lasting Effects for Children

People with implicit biases that enact policies create an unsafe learning environment for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx children. Implicit biases are unconscious attitudes, beliefs or stereotypes held about a group of people and can lead to unintentional discrimination towards people outside of one’s own racial group. One way that implicit bias surfaces in public schools is through teachers and administrators making discipline decisions. In North Dakota, 95 percent of teachers are non-Latinx and white and 92 percent of principals in North Dakota are non-Latinx and white. Teachers and administrators who lack meaningful training and interaction on other racial groups prior to working in the classroom bring their own implicit biases and racial stereotyping into the classroom. Subjective school policies, like disciplinary policies in North Dakota, allow these racial stereotypes and implicit biases to govern decisions about student outcomes like suspensions and referrals to law enforcement.

Footnotes

- Shockley, E, “FW: Referrals & out-of-school suspension Qs,” email to Xanna Burg, Sept 12, 2022, on file with author.

- North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, special data request for enrollment for K-12, out-of-school suspension days, and referrals to law enforcement by race and county, school year 2021-2022.