Policy Basics: Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA)

October 2025

In 1978, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) in response to the high number of American Indian children being removed from their homes and placed with families outside their community.1,2 The reform from ICWA began a shift away from decades of harmful child protection practices that forcibly separated and removed American Indian children from their families, often without any justified safety reasons. ICWA protects the best interests of American Indian children by preventing the unwarranted removal of children from their homes and keeping children connected to their families and Tribal culture when possible. The protections in ICWA consider the immediate needs of American Indian children and recognize that growing up connected to family and Tribal culture is in a child’s long-term best interest.

Experts and practitioners consider ICWA a “gold standard” for child protection practices and policies.3 For example, ICWA prioritizes an ongoing connection to family and community and stricter guidelines to ensure cases are actively working towards reunification.4 ICWA respects Tribal sovereignty and provides protections for children and families based on their legal status as citizens or members of Tribal Nations, not based on race. Unfortunately, the protections guaranteed by ICWA are inconsistently applied, and disparities still exist in protecting children’s safety and well-being. American Indian families are more likely to have their children removed from the home as the first step a caseworker takes and are less likely to be offered supportive interventions that would keep a family together.5

When a foster placement is needed, ICWA prioritizes keeping children connected to their family and Tribal culture, often referred to as kinship care. Research shows that kinship care has both short and long-term benefits. Children in kinship care experience fewer behavioral problems while adjusting to their new environment and less disruption in their education.6 In the long-term, children placed in kinship care experience better employment and education outcomes and are less likely to be incarcerated as adults.7

ICWA Repairs Past Harm to Tribal Communities

By the time ICWA was enacted in 1978, Tribal communities had endured decades of harmful policies due to systematic racism and colonization. For example, the federal government removed American Indian children from their families and sent them to boarding schools.8 Children were stripped of their culture, language, and identity at boarding schools. Another example, the federal government funded the Indian Adoption Project in 1958 to remove American Indian children from their homes, often without any justified safety reason, and place them for adoption with white families.9 These harmful policies continued for decades until reform started with ICWA.

In fact, North Dakota’s harmful child protection practices were among some of the worst in the country, and a driver for Congress to begin working on reform through ICWA. During a hearing on April 8, 1974, “a survey of a North Dakota Tribe indicated that, of all the children that were removed from that Tribe, only 1 percent were removed for physical abuse. About 99 percent were taken on the basis of such vague standards as deprivation, neglect, taken because their homes were thought to be too poverty stricken to support the children.”10 In 1976, North Dakota had the second worst (behind South Dakota) rate of American Indian children in foster care compared to all other children in the state. In North Dakota, 1 out of 28 American Indian children were in foster care, approximately 20 times higher than the rate for all other children (1 out of 554 children of other races).11 During this same time, 481 American Indian children from North Dakota were attending boarding schools. These children were also separated from their families and culture, although often not captured in the out-of-home placement data that included only foster care and adoption during this era.11

North Dakota’s State-Based ICWA Strengthens the Foster Care System

Despite the overwhelming evidence and expert support for ICWA practices, efforts to roll back these practices are, unfortunately, ongoing. In 2023, the Supreme Court ruled on the Brackeen v. Haaland case that challenged whether ICWA was constitutional.12 The Supreme Court upheld ICWA, and the protections for Indigenous children have remained in place at the federal level for now, but future challenges like the Brackeen case remain a threat. Policymakers in North Dakota recognized the importance of ICWA in light of the threat at the federal level and implemented a state-based ICWA policy during the 2023 session to ensure the gold standard of child protection practices remains in place regardless of changes at the federal level. Codifying ICWA into state law also streamlines priorities and processes for the judges and social service workers in North Dakota who interpret and implement these practices. In the 2023 session, House Bill 1536 passed with overwhelming support (all Senators voted in favor and all but one Representative voted in favor) to include the federal ICWA protections in state law.13

Highlights from the enrolled version of the 2023 House Bill 1536 included:

- Definitions of key terms, including that active efforts be made on behalf of American Indian children before being placed in state care, that clear and convincing evidence be provided before a child is removed from their home, and that qualified experts must testify that a child is at risk for serious emotional or physical damage if remaining at home.

- Clarification on the jurisdiction of child welfare cases, that Tribes should have jurisdiction for any child living on a reservation and should be transferred to Tribal jurisdiction when applicable, even if the child resides outside of a reservation. Language also clarified that a transfer out of Tribal court must have clear and convincing evidence of a hardship that transferring to Tribal court has that cannot be mitigated.

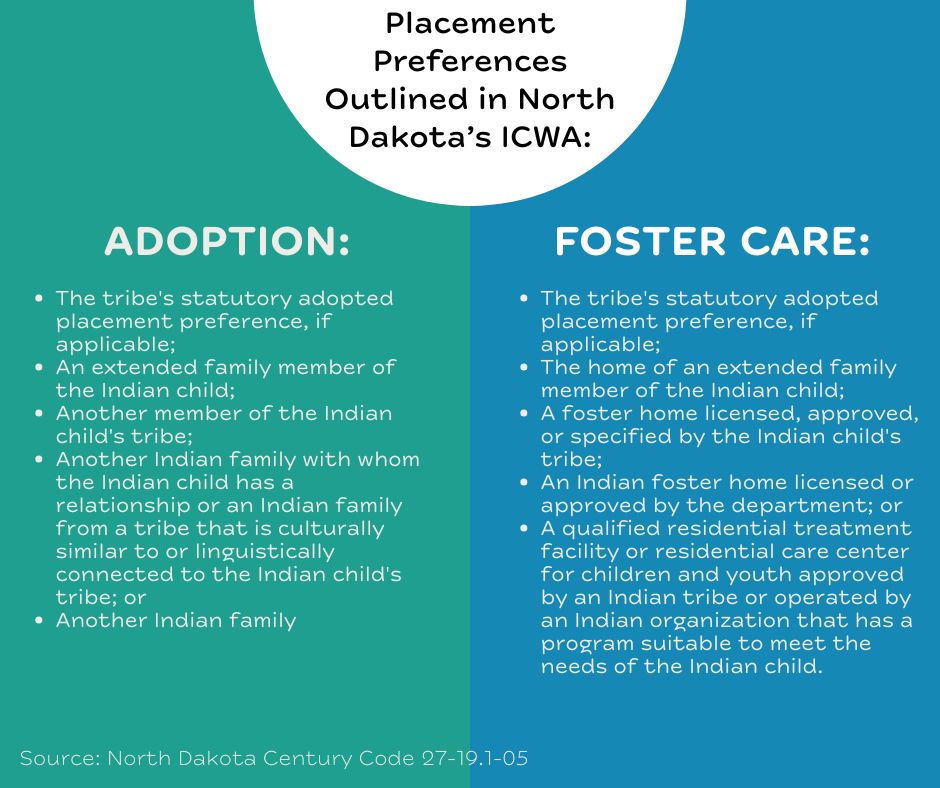

- Preferences for adoption and foster care placements. A notable addition in North Dakota’s preference list (that is not outlined federally) is a tier of priority for a placement with another family who the child already has a relationship with (e.g. teacher, coach, or neighbor) or a family from a Tribe that is culturally similar or linguistically connected. This additional tier recognizes that Tribes are unique and adds another layer to ensure a child is placed in a situation that preserves ties to their own Tribe’s unique culture.

In 2025, advocates brought forward small adjustments to strengthen the state-based ICWA laws in House Bill 1564.14 House Bill 1564 passed unanimously on the final vote in both chambers, indicating policymakers’ ongoing support for ICWA practices in North Dakota.

Changes from the enrolled version of the 2025 House Bill 1564 included:

- Removing the language, “non-foster care placement,” which had caused confusion in practice.

- Requires documentation of active efforts to begin during emergency removals, ensuring active efforts to prevent unwarranted removals begins as quickly as possible.

- Adds language to the adoption and foster care placement preferences, recognizing the Tribe’s placement preferences be followed as the top priority, if applicable. Otherwise, the outlined preferences remained the same from the 2023 version.

Disparities Continue to Exist in the North Dakota Foster Care System

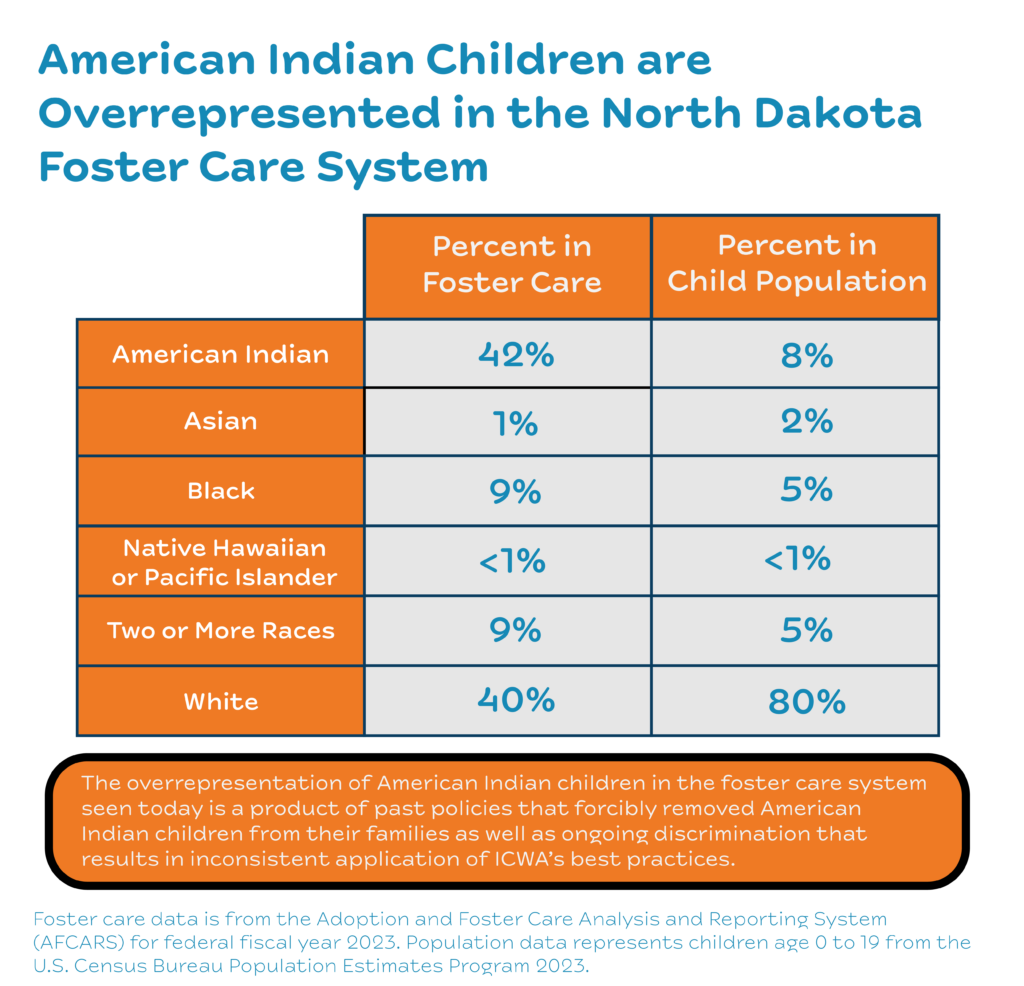

ICWA is an important part of protecting the best interests and well-being of children in North Dakota and provides protection for the more than 800 American Indian children in foster care.15 In North Dakota, American Indian children are in foster care at a rate five times higher than their rate in the general population due in part to ongoing discrimination and inconsistent application of ICWA’s best practices. In 2023, American Indian children made up 8 percent of the child population but 42 percent of the children in foster care.16 There are more American Indian children in foster care in North Dakota than there are white children in foster care, even though there are 10 times as many white children in the population.

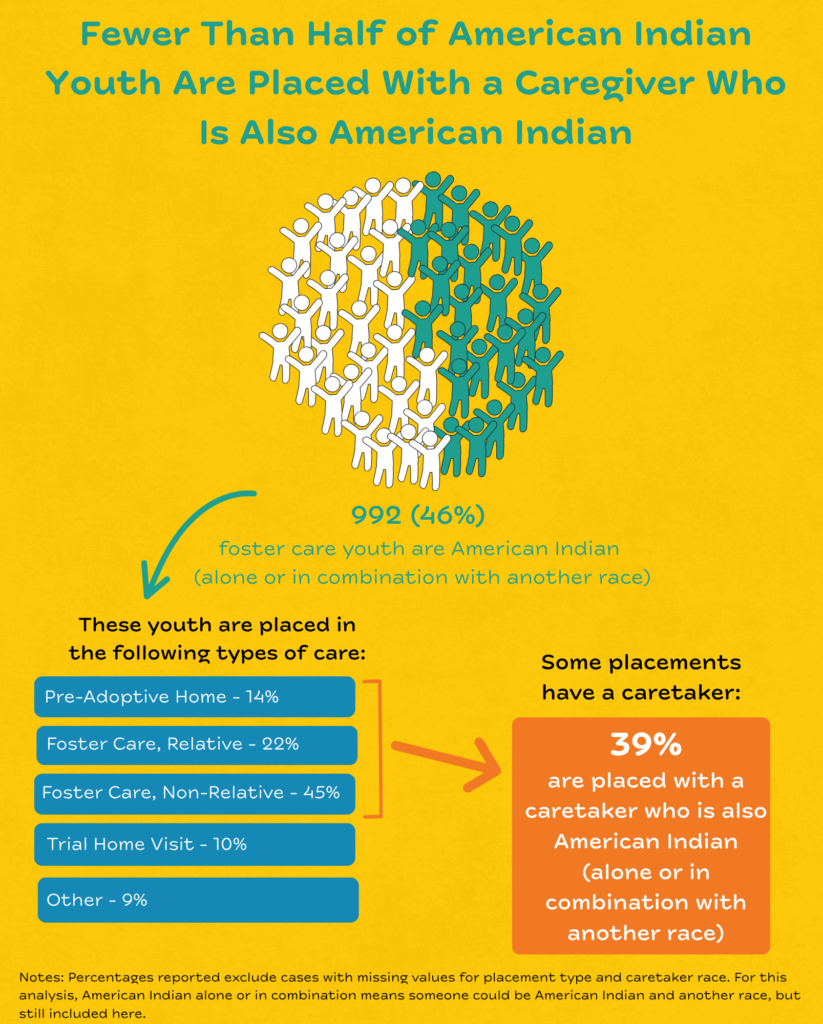

The ongoing disparities for children in foster care confirms why ongoing protections from ICWA are so critical. In addition, for children who are placed with a foster family, American Indian youth are less likely to be placed with a relative (33 percent) compared to their peers (42 percent).17 Less than half (39 percent) of American Indian youth in foster care have at least one caretaker who identifies as American Indian.17 These disparities show that many American Indian youth entering foster care are likely disconnected from their family, Tribe, and culture. Without ongoing ICWA protections, these data would certainly be worse; however, even with ICWA protections in place, systemic shifts are needed to ensure supports are in place for American Indian families.

Present-day Disparities Are Related to Chronic and Ongoing Underinvestment in Tribal Communities

Present-day disparities in the foster care system are also a result of the federal government failing to honor its treaty and trust responsibilities to provide services like health care, education, housing, and economic development in Tribal communities.18 The special trust relationship between the federal government and Tribal Nations obligates federal support for the general well-being of Tribal communities in exchange for Tribal land. Tribal communities historically have been left out of funding opportunities for child protection and prevention services that support healthy families. The federal government did not provide dedicated funds for child welfare to Tribal Nations until 1974, even though states began receiving funding in the 1930s.19 Even then, the funding was limited to only two grants per year. Starting in 1975, Tribal Nations were eligible for more widely available funding to support programs that protect the safety and well-being of children. While the federal funding structure today is more inclusive of Tribal communities, the amount of funds is still not enough to meet the needs.

All families need access to stable income, food, safe housing, and health care to thrive. However, chronic underfunding in Tribal communities for basic needs, like health care, impacts overall child well-being and family stability. For example, the federal government has chronically underfunded the Indian Health Service despite its trust obligation to provide health care established by treaties.19 This means comprehensive health care services are not always available for American Indian families when they need them, and parents or children in Tribal communities are often left without the preventative support and services they need.

ICWA is Essential for Supporting American Indian Children and Families in North Dakota

Considering the ongoing disparities in North Dakota’s foster care system, the protections guaranteed by ICWA are crucial as the state works to lessen these disparities. In addition, the federal government should fulfill its trust and treaty responsibilities and adequately fund child well-being and other services to support families in Tribal communities.

North Dakota policymakers should consider the disparities in the state’s foster care system when making decisions for funding state services. More funding is needed to support preventative services that help families before a child needs to be removed from their home. In addition, the state should consider providing higher funding to communities with a greater need to address disparities and begin undoing the harm Tribal communities and families have endured for decades.

Footnotes

- 5 U.S.C. Chapter 21 – Indian Child Welfare.

- National Indian Child Welfare Association, “What is ICWA?” accessed on Sep. 11, 2025.

- National Indian Child Welfare Association, “Setting the Record Straight: The Indian Child Welfare Act, Fact Sheet,” accessed on Sep. 30, 2025.

- Casey Family Programs, “How can child welfare systems apply the principles of the Indian Child Welfare Act as the “gold standard” for all children?” Apr. 1, 2022.

- National Indian Child Welfare Association, “Top 10 ICWA Myths Fact Sheet,” accessed on Sep. 11, 2025

- Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Stepping up for Kids: What Government and Communities Should Do to Support Kinship Families,” 2012.

- Lovett, N., Xue, Y., “Family First or the Kindness of Strangers? Foster Care Placements and Adult Outcomes,” Labour Economics, Mar. 6, 2018.

- Partnership with Native Americans, “Indian Boarding Schools in the United States Fact Sheet,” accessed Sep. 11, 2025.

- Palmist, C., “From the Indian Adoption Project to the Indian Child Welfare Act: the resistance of Native American communities,” 2011.

- “Problems that American Indian families face in raising their children and how these problems are affected by federal action or inaction,” testimony given to the Subcommittee on Indian Affairs, April 8-9, 1974. Special thanks to the National Indian Law Library who compiled an extensive, “Legislative History of the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978.”

- American Indian Policy Review Commission, “Report on Federal, State, and Tribal Jurisdiction,” July 1976.

- Native American Rights Fund, “Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) (Haaland V. Brackeen),” accessed on Sep. 11, 2025.

- North Dakota 68th Legislature, House Bill 1536, enacted on May 18, 2023.

- North Dakota 69th Legislature, House Bill 1564, enacted on Apr. 14, 2025.

- National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, “Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Report (AFCARS) AB Files, Federal Fiscal Years 2019-2023,” accessed by special request. The data is analyzed as a cumulative total, meaning throughout the entire fiscal year, the total number of children interacting with the foster care system is presented.

- Data reported for children identifying as American Indian alone. Similar disparities exist when comparing American Indian alone or in combination, making up 10 percent of the child population but 46 percent of the children in foster care.

- Data reported for children identifying as American Indian alone or in combination to more comprehensively understand children who have ties to Tribal communities, including those who may have multiple racial identities.

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding shortfall for Native Americans,” Dec. 2018.

- National Indian Child Welfare Association, “Tribal Leadership Series: Funding Child Welfare Services,” Feb. 2025.