The Impact of School Meals on Communities

October 2024

Families continue to need support for food

Although the poverty rate decreased in 2023, more than 15,000 North Dakota children lived below poverty (or $31,200 for a family of four).1 Many families above poverty also struggle to make ends meet, with more than one in five North Dakota children living below 200 percent of poverty (or $62,400 for a family of four).1 In 2023, one in three children received food from Great Plains Food Bank; the same year, the food bank served over 156,000 people in North Dakota, the most ever in its 40-year history.2 While other economic indicators suggest the economy in North Dakota is thriving, these measures do not fully capture the reality for every family.3 Attention is needed to specifically reach families and children struggling to afford basic needs.

Food security is complex and about more than simply having the resources to purchase food. Access to food, and specifically, access to the type of food that supports nutrition and culture, matters too. The food security landscape in Tribal communities today has been shaped by policy decisions across many generations that limited access to food, fertile land to grow and harvest traditional foods, and financial resources, and made it harder to remain connected to their culture and build community.4 For example, two Tribal Nations within North Dakota lived and relied on land along the Missouri River. The fertile land provided resources for agriculture and economic security. When the federal government built dams along the Missouri River in the mid-20th century, Tribal Nations were forced to give up land that was rightfully theirs and relocate to land without the same access to natural resources.5 The loss of this land was significant for food security, particularly when paired with a lack of investment in the areas where Tribal Nations were relocated.

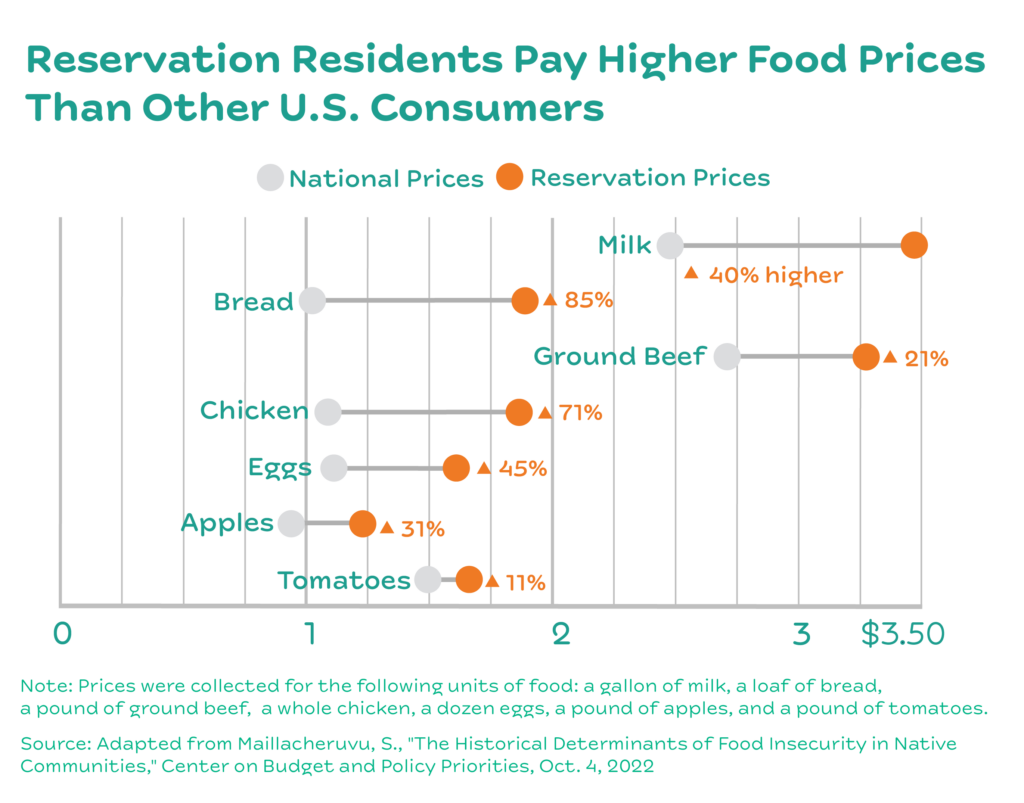

While data is not available for North Dakota, nationally, American Indian and Alaska Native people have food insecurity rates roughly double that of white people.4 Food prices in reservation communities are higher on average than national food prices. A study from 2018 found the cost of apples to be 31 percent higher in reservation communities, 45 percent higher for eggs, and 85 percent higher for bread.4

School meals are a critical safety net for families across the state

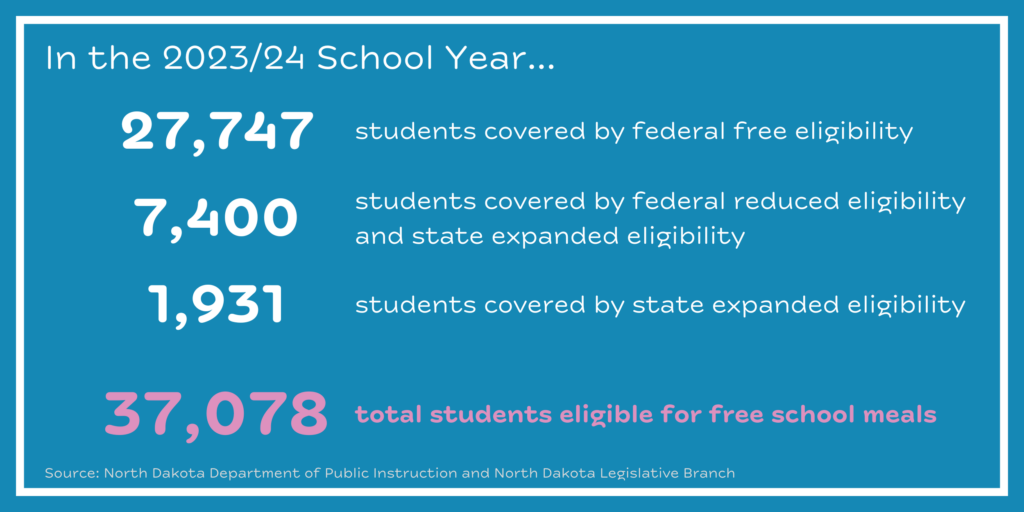

School meals and other summer food programs are an important source of healthy food for children of all incomes and serve as a critical safety net for families struggling across the state. The federal school lunch and breakfast program provides free or low-cost meals to families that qualify. North Dakota invested an additional $6 million in the school meal program over the last two years to cover reduced-cost meals and expand eligibility to even more children.6 Families up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level are now eligible to receive a free school meal, or about $62,400 for a family of four.7 In the 2023/24 school year, about 37,000 students were eligible for free school meals at public schools in North Dakota (35,147 qualified at the federal eligibility levels including 7,400 in the reduced-price category and 1,931 at the expanded eligibility covered by the state).8,9 Ongoing state investment will ensure a seamless continuation of the expanded eligibility for families.

A family typically qualifies for a free or low-cost meal by completing an application to determine their eligibility. Some schools use a different process though, called the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP).10 Schools use data that is already available to identify students eligible for federal food and benefit programs, like SNAP, TANF, or the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, or are in the foster care system, experiencing homelessness, or living in a migrant family. A school is eligible if at least 25 percent of the school falls into one of these categories. From a family’s perspective, CEP schools do not require paperwork, but all students can eat a free breakfast or lunch. From a school perspective, meals are reimbursed using a federal formula. If at least 62.5 percent of the school falls into one of the CEP categories, all meals are reimbursed at the highest federal rate.11 In North Dakota, 38 schools are participating in the CEP to provide free meals to all students for the current school year.12 Some schools may also take advantage of a federal flexibility in school meals called Provision 2. Using this flexibility, schools offer meals at no charge to students and only require applications from families every four years.13

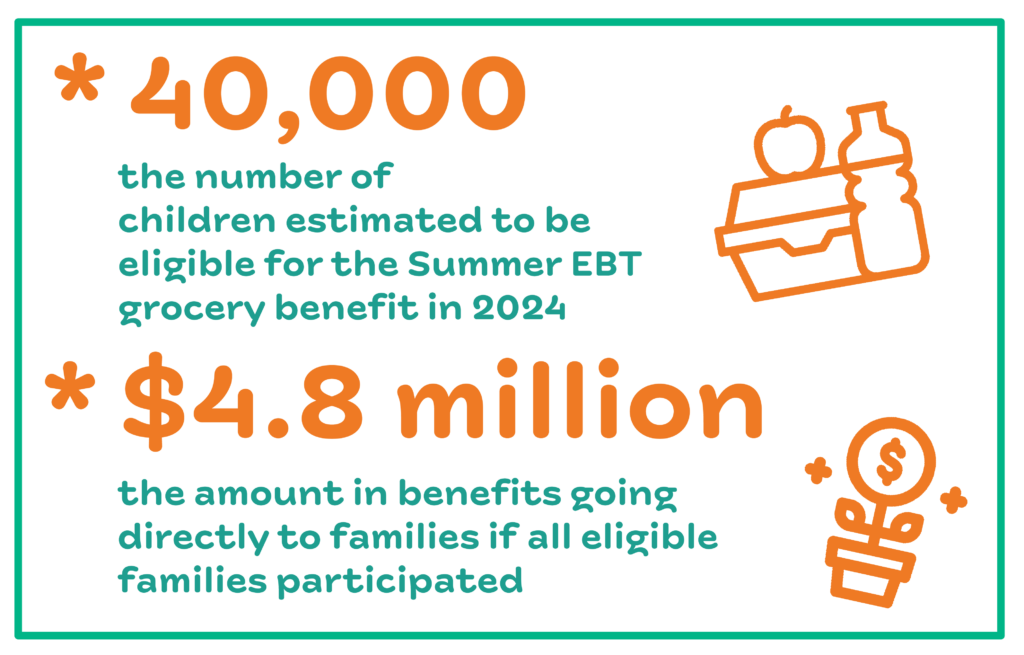

When school is out for the summer, summer food programs help fill the gap for many families. The Summer Food Service Program provides nutritious meals to children in eligible communities. In July 2023, about 4,200 students received a free lunch each day provided by the Summer Food Service Program.14 Compared to the school year, this is only 14 percent of students who receive a free or reduced-price meal. While summer meals are critical for families that can access them, many other families face barriers to using this program. A different but complimentary summer food program, Sun Bucks or Summer EBT, provides a $40 per month grocery benefit to families eligible for free or reduced-price meals. Approximately 40,000 children were estimated to be eligible for the Summer EBT grocery benefit in summer 2024, resulting in $4.8 million in benefits going directly to families if all eligible families participated.15

School meals play a unique role in food security for Tribal communities

Food security is an economic and racial justice issue. Addressing food security in North Dakota means recognizing the historical injustices that shape the food and economic resources available to Tribal communities today and designing policies that ensure solutions work for Tribal communities and BIPOC families.

In North Dakota, 11,997 American Indian or Alaska Native students attend public schools, making up 10 percent of overall enrollment.16 In fact, American Indian or Alaska Native students live and attend school in every county across the state. All types of schools are eligible to participate in the federal school meal program and the state expansion to 200 percent of the poverty level. This means public and non-public schools, such as private schools or schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Education, can participate.17

In North Dakota, 25 schools are located within one of the American Indian reservations in North Dakota, and the majority offer free meals to all students, either through CEP (18 schools), Provision 2 (four schools), or through a separate federal program that serves younger children (Child and Adult Care Food Program; one school).17,18 In the remaining two schools located within a reservation in North Dakota, families do complete an application to qualify for free or reduced-price meals. Eligibility at these two schools ranges from 50-60 percent of students.16 The state expansion of eligibility (to 200 percent of poverty) impacts these two schools, but largely did not change the school meal landscape for other students attending schools in reservation communities. Expanded eligibility does greatly impact American Indian students attending schools where free meals are not already available to all students. Of the 6,680 American Indian students attending one of these schools, 56 percent qualified for free and reduced-price meals in the last school year. Expanded eligibility helps reach more of the American Indian youth not currently participating.

Beyond expanded eligibility, other changes to school meals can help support Tribal communities, including providing categorical eligibility for free school meals to all enrolled members of Tribal Nations and increasing reimbursement rates for school meals served at schools on or near reservations. Both recommendations were included in the federal “Tribal Nutrition Improvement Act” introduced in 2022 which ultimately did not pass.19 Given the limited impact expanded eligibility has in Tribal communities, additional policy changes can work in tandem to support food security for Tribal Nations and more directly close the gap in economic and educational disparities for American Indian students.

Expanding access to school meals supports racial equity and can help close the gap in economic and educational disparities among other children of color too. Previously passed policies systematically limited opportunities for families of color with effects lasting generations and have resulted in present-day disparities in poverty rates for BIPOC children. Expanded eligibility for free school meals helps reach more families historically left out of economic support policies. With expanded eligibility up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level, estimates show that 59 percent of American Indian children, 72 percent of Black children, and 38 percent of children identifying as Asian, Native Hawaiian, Other, or two or more races are now eligible for school meals.20

Continue and build upon current school meal programs

Continuing the current school meal programs, including expanded eligibility to 200 percent and Summer EBT, will allow a seamless continuation of benefits for families. This means a continued state investment to cover reduced-cost meals and the full cost for families above the federal eligibility level. Policymakers can build on progress made in recent years by offering healthy school meals for all students. Eight other states have permanent policies in place to provide school meals to all, and research shows when free meals are offered to all students, participation in the program increases and academic outcomes improve.21,22

Policymakers should consider ways to implement changes included in the federal “Tribal Nutrition Improvement Act of 2022” at the state level to further support Tribal communities directly, including categorical eligibility for free school meals for enrolled members of Tribal Nations and an increase in reimbursement rates for school meals served at schools on or near reservations.19

Footnotes

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Age by Ratio of Income to Poverty Level in the Past 12 Months, 2018-2022 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B17024.”

- Great Plains Food Bank, “Our Annual Report,” 2023.

- North Dakota Office of the Governor, “North Dakota leads nation in growth of earnings, real GDP in latest report from Bureau of Economic Analysis,” July 12, 2023.

- Maillacheruvu, S.U., “The Historical Determinants of Food Insecurity in Native Communities,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 4, 2022.

- State Historical Society of North Dakota, “Lesson 1: Changing Landscapes, Topic 1: Garrison Dam and Diversion, Section 3: The Taking,” accessed Apr. 18, 2022.

- North Dakota KIDS COUNT, “2023 Legislative Session: Children’s Well-Being Bills,” Aug. 2023.

- North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, “Child Nutrition and Food Distribution Programs Income Eligibility Guidelines, July 1, 2024 to June 30, 2025.”

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Eligible recipients of free or reduced-price lunch in North Dakota, 2023/24.”

- North Dakota Legislative Branch, “Interim Update – Compliance Report, Department of Public Instruction Budget No. 201,” accessed on Sep. 18, 2024.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Community Eligibility Provision,” accessed on Sep. 18, 2024.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Community Eligibility Provision Slider Tool,” accessed on Sept. 18, 2024.

- North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, “2024 Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) Annual Notification of Schools,” accessed on Sep. 18, 2024.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, “Provision 2 Guidance National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs,” accessed on Sep. 18, 2024.

- Food Research & Action Center, “Hunger Doesn’t Take a Vacation, Summer Nutrition Status Report,” Aug. 2024.

- Food Research & Action Center, “The Summer EBT Program Would Reduce Summer Hunger in North Dakota,” Dec. 2023.

- North Dakota KIDS COUNT calculations using North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, “1-InclusiveEnrollment.xlsx,” KIDS COUNT information request, received on Feb. 26, 2024, on file with author.

- Schloer, L, Child Nutrition and Food Distribution Programs, “RE: school meals and tribal communities,” email to Xanna Burg, North Dakota KIDS COUNT, Sep. 12, 2024, on file with author.

- North Dakota KIDS COUNT calculations using North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, “School Directory Contact Information, School Year 2023-2024, Jan. 4, 2024,” downloaded on Sep. 11, 2024. Tribal reservations were identified using U.S. Census Bureau, “2023 TIGER/Line Shapefiles: American Indian Area Geography, American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian Area,” downloaded on Sep. 11, 2024.

- U.S. Congress, “S.4625 – Tribal Nutrition Improvement Act of 2022,” accessed on Sep. 18, 2024.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Analysis of Public Use Microdata Sample for 2018-2022.

- Bylander, A., “States Show Us What Is Possible With Free Health School Meals for All Policies,” Food Research & Action Center, Sep. 6, 2023.

- Food Research & Action Center, “School Meals are Essential for Student Health and Learning,” May 2021.