Uncovering North Dakota's Youth Mental Health Landscape

September 2024

Mental health is an important part of overall health and well-being, with mental health challenges impacting many areas of a child’s life as they grow up.1 Youth in North Dakota report facing more challenges with mental health in the last few years due in part to added stress faced during the pandemic, such as loss of connection to peers and disruption to systems and services that support youth.2 Heightened parental stress from lost wages and rising costs can also impact children.

A dual focus is needed to support youth mental health in North Dakota. First, strong support systems and prevention efforts are needed to help young people cope with challenges as they come up, which can help avoid more serious mental health conditions in some cases. Second, for youth who are experiencing a mental health disorder, proven treatments and services exist, yet almost half (46 percent) of children with a mental health condition in North Dakota do not receive treatment.3 A focus on providing accessible, affordable, and supportive treatment options and crisis services is an ongoing need for North Dakota youth and their families as they navigate the mental health system across the state.

North Dakota’s mental health landscape is complex

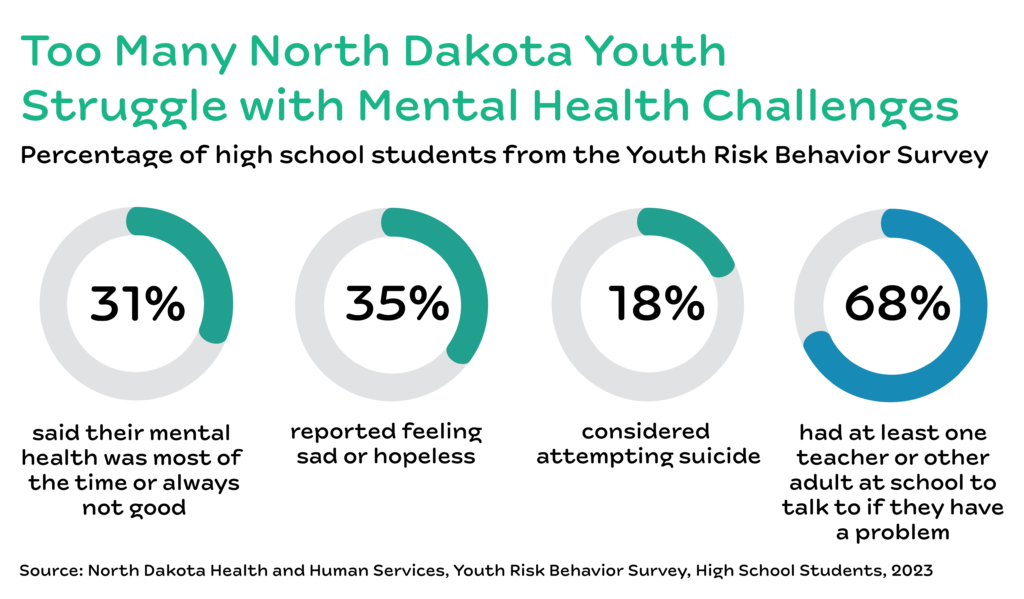

North Dakota youth report higher rates of mental health conditions compared to five years ago, with 23 percent of children and adolescents experiencing one or more mental health conditions.3 More than a third, or 35 percent, of high school youth reported feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in the last year.4 In 2023, 18 percent of high school students seriously considered suicide in the last year.4 Certain groups of people report even higher rates of mental health outcomes, a result of years of added barriers that make it harder to access support systems and treatment. Youth of color and LGBTQ+ youth report higher rates of feeling sad or hopeless and seriously considering suicide.4,5 The teen suicide death rate in North Dakota has decreased during the most recent three-year period (2020-2022) to 13.7 per 100,000 teens.6

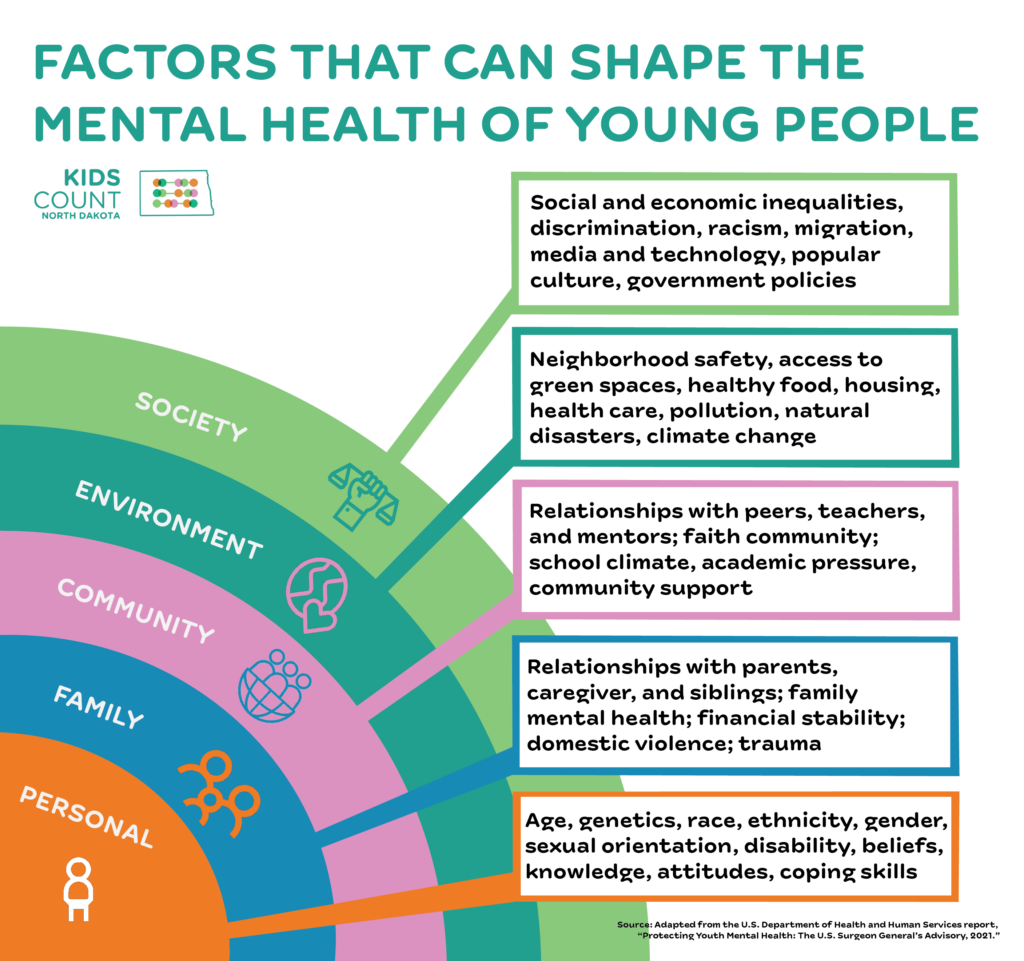

The data can be overwhelming and shows just a small picture of outcomes related to mental health, a complex topic that requires looking at both clinical outcomes as well as protective factors that can help lessen mental health challenges when they arise. A more complete picture of the youth mental health landscape in North Dakota includes factors across many levels beyond individual outcomes, such as those shaped by communities and the places youth spend their time.

For example, a key protective factor is the relationships youth have with family, peers, teachers, and other mentors in their community. More than two thirds (68 percent) of high school students in North Dakota had at least one teacher or other adult at their school they could reach out to if they had a problem.4 An important consideration is how to reach the remaining third of students lacking a trusted adult at school. Only 21 percent of high school youth struggling with mental health (feeling sad, empty, hopeless, angry, or anxious) said they would most likely talk with their parent or other adult family member about their feelings.7 This number drops down to only 6 percent for transgender students, 7 percent for youth identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, and 10 percent for American Indian youth.7,8

Another protective factor for youth is making sure young people remain connected to school, employment, or other systems of support. Programming like extracurricular activities or afterschool and summer programs for school-age youth is one example of community support that may be overlooked in the mental health conversation. Estimates show that for every child currently in an afterschool program, two more are waiting to get in, signaling a need for more safe and enriching opportunities for North Dakota’s youth.9 Nationally, youth from lower-income families are less likely to participate in extracurricular activities, highlighting a need to focus on access to extracurricular activities throughout communities as well.10

Supports and hurdles for youth mental health in North Dakota

In 2021 the U.S. Surgeon General published an advisory on youth mental health, highlighting concerns about declining trends in mental health outcomes. This advisory broadly discussed the complex reasons behind the worsening data:2

“Scientists have proposed various hypotheses to explain these trends. While some believe that the trends in reporting of mental health challenges are partly due to young people becoming more willing to openly discuss mental health concerns, other researchers point to the growing use of digital media, increasing academic pressure, limited access to mental health care, health risk behaviors such as alcohol and drug use, and broader stressors such as the 2008 financial crisis, rising income inequality, racism, gun violence, and climate change.”

A web of programs and services exists to support mental health across the state. For example, North Dakota launched the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, with more than 7,000 people utilizing these services through December 2023, including 29 percent of youth and young adults.11 Schools also serve as a critical piece of the mental health support landscape, with a behavioral health coordinator in each district, Behavioral Health School Grants, and training and technical assistance available to schools. North Dakota Department of Health & Human Services also oversees Regional Human Service Centers and prevention programs that support youth mental health.11

While supports exist across the state, youth and families also face hurdles as they navigate through treatment options and available services. Limited access to providers and support services, particularly those that serve youth, is a known and ongoing challenge across the state.12 In 2023, state policymakers passed an interim study bill on mental health care for children to better understand where gaps exist between home- and community-based services.13

Economic challenges families face also create hurdles for youth mental health; when families struggle to make ends meet, it adds additional stress on the whole family. With North Dakota’s rising child poverty rate, the housing affordability crisis, and a heightened need for food assistance, many families continue to struggle.14,15,16 Other economic indicators suggest the economy in North Dakota is thriving (for example, North Dakota had the third highest personal income growth out of any state in 2023), but worsening economic outcomes for those living on low incomes suggest that attention is needed to specifically reach families and youth that need it the most.17 Supporting a family’s economic security also supports improved mental health outcomes for youth.18

Gaps exist across North Dakota in mental health providers and programs

State leaders must invest in a system that has both preventative support as well as treatment options when and where young people need them. Two statewide resources compile a list of mental health providers and resources: 211 and the North Dakota Mental Health Program Directory run through the Department of Health and Human Services.19,20 Between these two sources, 21 counties have no mental health providers listed that specifically work with youth. This means 16,637 youth across the state live in a county with no listed youth mental health providers.21 More broadly, most counties in North Dakota (46 counties) are considered mental health care professional shortage areas, meaning too few mental health professionals work in an area relative to the population, factoring in higher-need populations.22,23

Many children rely on school-based mental health resources, including school counselors as an important part of the mental health care system for youth in North Dakota. However, the need for school-based mental health support in many communities exceeds the capacity of school counselors. An ideal ratio of school counselors to students is 1:250, yet statewide North Dakota has a ratio of 1:298.24,25 Using the school counselor directory published by the Department of Public Instruction, 35 counties do not meet the 1:250 recommendation, representing 108,052 students enrolled in North Dakota’s public schools, or 87 percent of total school enrollment.26,27

While gaps exist across North Dakota in having enough mental health providers in the places young people live, other barriers also impact the ability to receive needed services. The cost of accessing mental health care may be out of reach for many families, particularly the 10,000 children without health insurance.28 While data for children is not available, more than a third (36 percent) of adults in North Dakota who needed mental health treatment did not receive care because of cost.29 Additionally, sifting through an already-limited pool of providers to find someone who supports your culture or identity makes it particularly challenging for certain youth to access care.

LGBTQ+ youth face more barriers to mental health support

LGBTQ+ youth face unique challenges and additional barriers to health and wellness. Historically, LGBTQ+ youth have not always been represented in the available data, even though LGBTQ+ people have always lived in North Dakota. Lack of data translates to a limited understanding of the outcomes and experiences of LGBTQ+ youth. The data estimates that 10,500 youth identify as LGBTQ+ within middle and high schools, or 15 percent of high school students and 19 percent of seventh and eighth-grade students.30

LGBTQ+ youth in North Dakota report fewer protective factors compared to their peers. LGBTQ+ youth are less likely to eat with or talk to their family compared to their straight peers and are more likely to be hurt by their family.31 LGBTQ+ youth also experience more bullying at school or online and are less likely to report having a teacher or adult at school they can talk to if they have a problem.8 Supportive school and family environments are a key protective factor for youth when challenges arise. Without better support systems and protective factors for LGBTQ+ youth, many fare worse in mental health outcomes. LGBTQ+ youth are more likely to have poor mental health, feel sad or hopeless, and consider suicide.

In North Dakota, the political landscape consistently limits LGBTQ+ people’s access to health care and welcoming communities. For example, House Bill 1254 criminalizes providing medical care to transgender youth for the purpose of changing or affirming a child’s perception of their sex, making it even harder to access health care that supports a transgender youth’s mental and overall health.32 LGBTQ+ youth need more mental health care options that support their unique needs and experience, and they need leaders in their communities and schools working to create safe, welcoming, and supportive environments.

BIPOC youth also face more barriers to mental health support

As a result of generations of discrimination and racism, families and children of color in North Dakota face more barriers to health and wellness. For example, the federal government has failed to honor its treaty and trust responsibilities to provide health care to American Indians, resulting in a chronically underfunded tribal health care system that leaves many American Indian families without access to a full range of medical care when they need it.33 Unfortunately, the examples do not stop there. The federal government intentionally assimilated American Indian families into the dominant culture, through policies like boarding schools or unfair child protective services practices.34 This made it harder for Indigenous youth to remain connected to their communities and culture, limiting the protective effect a feeling of belonging has as well as limiting more culturally relevant health care. More broadly, people of color have more limited access to providers and hospitals, have more difficulty finding culturally appropriate care, and experience lower quality of care.35 In addition to these specific barriers within health care, generations of barriers to economic security have made it harder for families of color to build wealth and live without the added stress that economic insecurity brings.

More than one out of four (27 percent) children in North Dakota are BIPOC, a growing demographic in North Dakota.36 Yet BIPOC youth report fewer protective factors compared to their peers. For example, students of color are less likely to have a teacher or other adult in their school they can talk to if they have a problem.4 All school staff, regardless of race, play a role in creating safe spaces for BIPOC students; however, ensuring school staff come from the communities they serve is one strategy to build stronger support for youth of color. In North Dakota, only 5 percent of public school teachers are BIPOC, even though BIPOC students make up 27 percent of public school enrollment.26,37 Mental health outcomes for BIPOC youth are directly tied to the limited support systems shaped by generations of harmful policies. More than a third (38 percent) of Indigenous youth report their mental health was most of the time or always not good in the past month, and half report feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for more than two weeks in the last year.4 Of the Indigenous students reporting feeling sad or hopeless, only 12 percent get the kind of help they need most or all of the time.4 Asian, Latinx, and multiracial youth also report higher rates of poor mental health.

North Dakota has options to improve youth mental health

Better support for youth mental health is an urgent priority in North Dakota. Everyone can play a role in improving youth mental health in our state. Listening to the voices of young people can help give an even deeper understanding of mental health challenges, supports, and what solutions are needed.

Parents and Other Adults

- Build meaningful and trusting relationships with youth. Research shows that the most important factor for resiliency in children is a committed relationship with a supportive adult.2

Schools and North Dakota’s Education System

- Ensure North Dakota schools have the funding and resources to recruit, retain, and train school staff who support children’s mental health, including school counselors and positions like instructional assistants who provide direct support to students.

- Create positive, safe, and affirming school environments, particularly for LGBTQ+ and BIPOC students.

- Provide school staff opportunities for training and professional development around best practices for supporting youth mental health, including specific information on the unique needs of LGBTQ+ and BIPOC students.

Policymakers and Other State or Local Decisionmakers

- Ensure kids and families have their basic needs met to decrease family stress. This includes reducing child poverty and improving access to healthy food and affordable housing.

- Ensure all children have comprehensive and affordable coverage for mental health care, including reaching the 18 percent of children eligible but not currently enrolled in Medicaid.38

- Work toward all regional human service centers and clinics becoming certified community behavioral clinics.39

- For state-based mental health programs, consider how they can better reach LGBTQ+ and BIPOC youth. Working alongside these communities and listening to those with lived experience will help shape policies that best reach those left out in the past.

- Ensure parents and families have the tools and resources they need to foster strong relationships with young people as they grow up, particularly at a time when parents are experiencing heightened stress and mental health challenges as well.40

Footnotes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Mental Health: Poor Mental Health Impacts Adolescent Well-being,” May 1, 2024.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory,” 2021.

- Population Reference Bureau analysis of National Survey of Children’s Health, 2016, 2017, 2021, 2022 enhanced files, on file with author.

- North Dakota Department of Health and Human Services, “2023 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Results, North Dakota High School Survey.”

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “High School YRBS: North Dakota 2021 Results.”

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Teen Suicide Death Rate in North Dakota,” 2020-2022.

- Data represents 2021 since this question was not available in the 2023 YRBS analysis. North Dakota Department of Health and Human Services, “2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Results, North Dakota High School Survey.”

- Seidler, F., “YRBS 2021 Complete LGBTQ+ Data Overview.”

- Afterschool Alliance, “North Dakota After 3pm,” 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP),” SIPP 2020.

- Sagness, P., North Dakota Department of Health and Human Services, “Study of Mental Health Care for Children,” presentation to the Interim Human Services Committee, Apr. 8, 2024.

- McCleary, C., North Dakota Mental Health Advocacy Network, “Study 3017 Testimony,” public comment submitted to the Interim Human Services Committee, Aug. 29, 2023.

- North Dakota Legislative Council, “Study of Inpatient Mental Health Care for Children – Background Memorandum,” prepared for the Human Services Committee, Aug. 29, 2023.

- 13 percent of children lived in poverty in 2022. KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Children in poverty in North Dakota,” 2022.

- 19 percent of children live in families who spend more than 30 percent on housing. KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Children living in households with high housing cost burden in North Dakota,” 2022.

- Great Plains Food Bank served the most number of people in their 40-year history. Great Plains Food Bank, “About Us: Our Annual Report, 2023.”

- North Dakota Office of the Governor, “North Dakota leads nation in growth of earnings, read GDP in latest report from Bureau of Economic Analysis,” Jul. 12, 2023.

- Hodgkinson, S., et al., “Improving Mental Health Access for Low-Income Children and Families in the Primary Care Setting,” Pediatrics, Jan. 2017.

- Illich, J., FirstLink, “RE: FirstLink – Mental Health,” email to Xanna Burg, North Dakota KIDS COUNT, May 20,2024, on file with author.

- North Dakota Department of Health & Human Services, “North Dakota Mental Health Program Directory,” accessed on Apr. 24, 2024.

- For the 21 counties with no youth mental health providers, population age birth to 17 is added up for a total of 16,637 youth living in a county with no youth mental health provider, as of April 2024 for the DHHS directory and May 2024 for the FirstLink community directory. Population data is from: KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Child population by age group in North Dakota,” 2023.

- North Dakota Health & Human Services, “North Dakota Mental Health HPSA – 2023.”

- U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, “Health Workforce Shortage Areas,” data as of Aug. 20, 2024.

- American School Counselor Association, “School Counselor Roles & Ratios,” accessed on Aug. 21, 2024.

- American School Counselor Association, “Student-to-School-Counselor Ratio 2022-2023.”

- Enrollment data represents students in public schools for grades preschool through twelfth grade. North Dakota KIDS COUNT calculations using North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, “1-InclusiveEnrollment,” North Dakota KIDS COUNT information request, received on Feb. 26, 2024, on file with author.

- North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, “School Directory Contact Information,” as of Jan. 4, 2024.

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Children without health insurance by age group in North Dakota,” 2022.

- KFF, “Adults Reporting Unmet Need for Mental Health Treatment in the Past Year Because of Cost,” 2018-2019.

- Seidler, F., “North Dakota 2022 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System LGBTQ+ Report.”

- Seidler, F., “Family Social Capital,” data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data.

- North Dakota 68th Legislature, “An act to create and enact chapter 12.1-36.1 of the North Dakota Century Code, relating to the prohibition of certain practices against a minor,” HB 1254, enacted on Apr. 25, 2023.

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding shortfall for Native Americans,” Dec. 2018.

- North Dakota KIDS COUNT, “Policy Basics: Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA),” Nov. 2022,

- Artiga, S., Pham, O., Orgera, K., Ranji U., “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: An Overview,” Kaiser Family Foundation, Nov. 10, 2020.

- KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Child population by race and ethnicity in North Dakota,” 2023.

- National Center for Education Statistics, “National Teacher and Principal Survey, Teachers’ race/ethnicity: Percentage distribution of public K-12 school teachers, by race/ethnicity and state: 2020-21.”

- KFF, “Medicaid/CHIP Child Participation Rates,” 2019.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics,” accessed on Aug. 21, 2024.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Parents Under Pressure, The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Mental Health & Well-Being of Parents,” 2024.

- The Trevor Project, “The Mental Health and Well-Being of Indigenous LGBTQ Young People,” Nov. 30, 2023.